Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP)

Pelvic organ prolapse at a glance:

- Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) happens when one or more of a woman’s organs in the pelvic area drops (prolapses) from its normal position to push against the walls of the vagina.

- The different types of POP, discussed below, are related to the organ that drops out of position: the bladder, urethra, uterus, vagina, small bowel and/or rectum.

- Prolapse occurs when the downward pressure of the pelvic organs is greater than the strength of the muscles and ligaments that support the vagina. These supporting structures are located at the vaginal opening, the mid-vagina and at the top of the vagina.

Suffering from pelvic organ prolapse? We can help.

Causes of pelvic organ prolapse

Causes of POP include vaginal childbirth, trauma, nerve damage, muscle strain, increased abdominal pressure (often due to being overweight, chronic cough, or straining), and age, which naturally weakens muscles. Older women are more likely to experience POP, and the number of women affected is increasing due to longer lifespan.

Other risk factors include smoking and previous pelvic area surgeries, such as a hysterectomy.

Symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse

Women with pelvic organ prolapse symptoms often vaguely experienced feelings of discomfort in the pelvic area that may be constantly present or more apt to appear after a long day of standing or after heavy physical exercise.

Noted symptoms include:

- Feeling pressure against the vaginal wall (feels like sitting on an egg)

- A pulling or stretching feeling in the groin that may worsen the longer you stand

- Pain in the lower back

- Heightened discomfort when straining

- Urinary incontinence or needing to urinate frequently

- Bowel problems, such as constipation

- A bulge of tissue that may protrude from the vagina in some cases

Treatments for pelvic organ prolapse

Treatments generally attempt to correct the area of lost vaginal support and to provide relief from symptoms. Treatments fall into five categories:

- Watchful waiting (some symptoms go away on their own)

- Physical therapy and behavior changes (exercises, diet, weight control)

- Insertion of a vaginal supporting device

- Medications

- Surgery

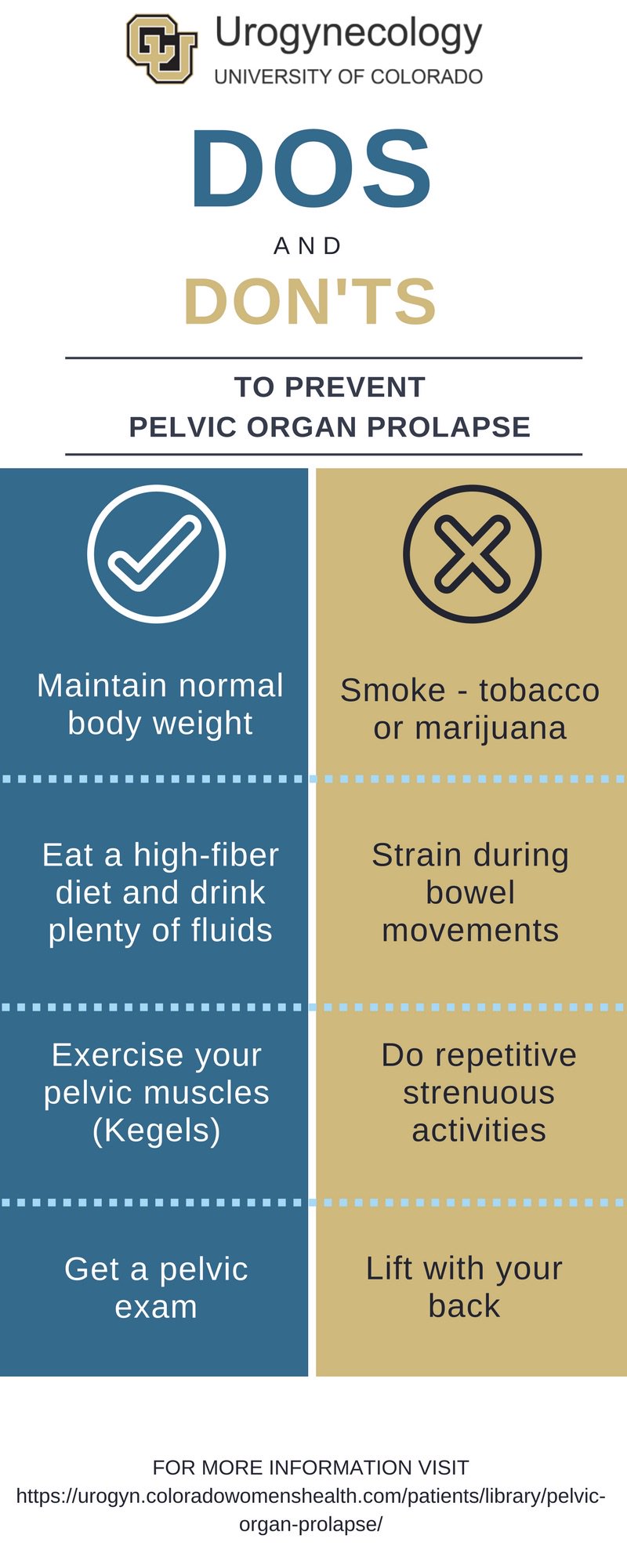

The patient can often manage milder cases of pelvic organ prolapse by maintaining the proper weight, not smoking, doing pelvic floor exercises, avoiding heavy lifting and strains on the pelvic area, and reducing caffeine, which causes frequent urination.

Laura was reluctant to undergo surgery for her pelvic organ prolapse, thinking that the relief wouldn’t last.

Read her Success Story

Types of pelvic organ prolapse

Cystocele

Cystocele is a prolapse of the bladder into the front wall of the vagina due to a weakening and stretching of supporting tissues and muscles. Also called a prolapsed bladder, a cystocele is often caused by aging, genetic factors that cause some women to be born with weaker connective tissues, and by straining that occurs during childbirth, heavy lifting and chronic constipation or violent coughing.

In addition to the general symptoms listed above, signs of a cystocele may be discomfort and pain in the pelvic area, repeated bladder infections, and the feeling of not having emptied the bladder after urination.

Mild cases of cystocele may call for monitoring, weight control and physical therapy to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, such as Kegel exercises. More advanced cases of cystocele may require:

- A pessary, which is a ring-like device fitted and inserted into the vagina to support the bladder, then routinely cleaned and reinserted by the patient. Local estrogen applications often accompany use of a pessary.

- Surgery, which is often done vaginally. The procedure involves lifting the bladder back into place and tightening the ligaments and muscles of the pelvic floor to increase support. Tissue grafts and synthetic mesh are often used to help strengthen weakened supporting tissue.

Urethrocele

An urethrocele occurs when tissues of the urethra drop down into the vagina. Also called a urethral prolapse, an urethrocele often happens in conjunction with a cystocele, or with other types of pelvic organ prolapse. The symptoms, causes, treatments and risks associated with both cystoceles and urethroceles are the same. Urethroceles and cystoceles are easily detected in a physical exam.

Enterocele

An enterocele happens when a space develops between the vagina and the rectum allowing the small bowel (small intestine) to drop into the top of the vagina, creating a bulge. Women who have had their uterus removed (hysterectomy) are most likely to experience an enterocele prolapse. Other types of prolapse often occur with an enterocele.

Mild cases of enterocele usually show no symptoms. Mild symptoms can frequently be managed by exercises and nonsurgical treatments prescribed for pelvic organ prolapse cases. Severe enterocele cases will be accompanied by the POP symptoms described above.

Use of a fitted pessary or surgery may be required for an enterocele. Surgery for enterocele involves supporting the prolapsed small bowel. An enterocele is unlikely to recur once surgically addressed.

Rectocele

Rectocele prolapse occurs when the wall of tissue (fascia) separating the rectum from the vagina weakens and, typically, the front wall of the rectum pushes into the vagina. Also called a posterior prolapse, a rectocele may involve a small drop, in which no symptoms may be present, or a large drop of the rectum, which can create a bulge of tissue through the vagina opening.

Self-treatments for a mild rectocele include Kegel exercises, maintaining proper weight, and avoiding constipation, heavy lifting and straining during bowel movements. Insertion of a pessary to help provide support may be necessary. Surgery may be appropriate for more severe cases. Signs of a rectocele that require attention include:

- Presence of soft tissue that may or may not bulge through the vaginal opening

- Difficult bowel movements, requiring finger pressure on the tissue bulge to facilitate the bowel movement

- Rectal feelings of pressure, fullness or a sense that the bowel has not emptied after a movement

- A loosening of vaginal tone during sex.

Uterine prolapse

Uterine prolapse occurs when the uterus drops into the vagina due to weak supporting tissue structure. Sometimes part of the uterus protrudes from the vagina.

Uterine prolapse often occurs in postmenopausal women who have experienced tissue damage from one or more vaginal deliveries, particularly with a large baby. However, any woman can experience uterine prolapse, which includes the same risk factors and causes as other forms of pelvic organ prolapse.

Mild cases of uterine prolapse require observation but no treatment. If symptoms become aggravating, treatments may be beneficial. These range from exercises to use of a pessary to surgery, sometimes minimally invasive surgery via a small abdominal incision. Removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) is sometimes necessary.

Learn More about Uterine Prolapse

Vaginal vault prolapse

Vaginal prolapse occurs when the upper portion of the vagina drops into the vaginal canal, sometimes protruding outside the vagina. Vaginal vault prolapse is due to a weakening of the pelvic supporting tissues and muscles that support the top of the vagina, which then loses its normal shape and prolapses downward.

Vaginal vault prolapse most often occurs in women who have had a hysterectomy. It may also occur along with other types of pelvic organ prolapse.

Primary symptoms of vaginal vault prolapse include backache, tissue mass bulging into or from the vaginal canal, urinary incontinence, vaginal bleeding, and pain during intercourse. Surgery is the primary treatment and involves attaching the upper vagina to either the lower abdominal wall, the ligaments of the pelvis or to the lower spine (lumbar).

Learn More about Vagina Vault Prolapse